The State of AI 2026: Part III - When the Training Wheels Come Off

Moving from simple chat to persistent autonomy, 2026 defines the arrival of the agent colleague. We explore the memory breakthroughs, tool-calling opportunities and more

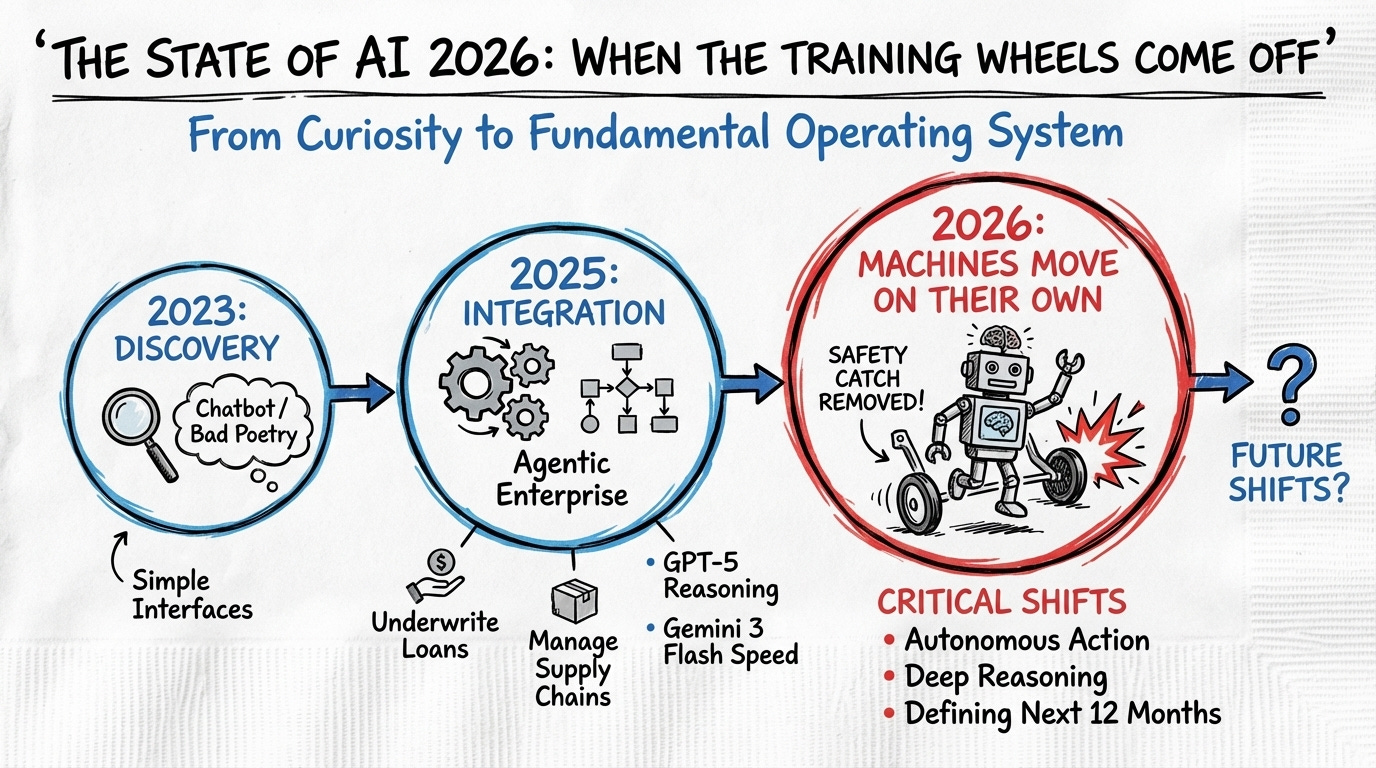

The shift from 2025 to 2026 feels less like a step forward and more like the removal of a safety catch. For the past three years, we have watched artificial intelligence evolve from a curiosity that could write bad poetry into the fundamental operating system of modern business. If 2023 was about discovery and 2025 was about integration, 2026 is the year the machines begin to move on their own.

In the part 1 and part 2 of this series, we explored how the “Agentic Enterprise” emerged from the chaos of early experimentation. We charted the journey from simple chat interfaces to complex, multi-step workflows that can underwrite loans and manage supply chains. We also examined the raw capabilities that power this transition, from the reasoning depth of GPT-5 to the blistering speed of Gemini 3 Flash. Now, we turn our eyes to the future. What follows are the critical shifts that will define the next twelve months for those leading companies and those writing the code that powers them.

The Executive View: The Velocity Gap

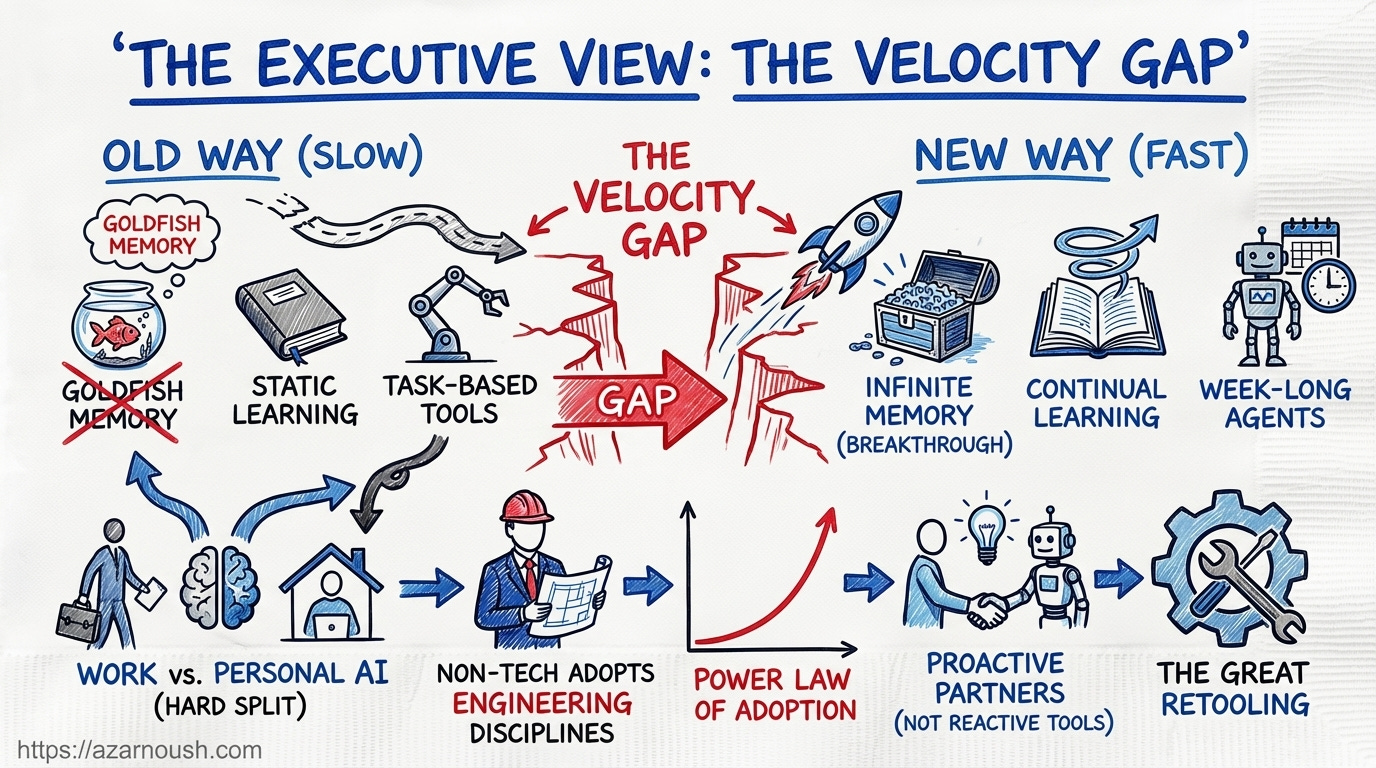

For leadership teams, 2026 will be defined by a widening chasm between organisations that treat AI as a tool and those that treat it as a colleague. The predictions below highlight a move away from passive efficiencies toward active, autonomous value creation.

A Significant Breakthrough in AI Memory

For years, the “goldfish memory” of Large Language Models has been a persistent bottleneck. We are now on the cusp of an application layer solution that will likely be perceived as a memory breakthrough. By mid 2026, compression tools and agentic systems using flat files will allow systems to retain a fidelity of context that feels nearly infinite. This means the end of repeating yourself; your digital assistant will simply “know” the history of every project, decision, and meeting, radically improving the competence of long-term planning agents.

The Transition to Continual Learning

The concept of a “frozen” model, stuck with a knowledge cutoff from six months ago, is becoming obsolete. We will see a shift toward systems that learn as they go. Much like a new employee who starts rough but improves daily, software will become “sticky” and valuable not just because of its features, but because of its accumulated experience. A model that understands your specific business logic because it has watched you work for a week is infinitely more valuable than a smarter, generic model that knows nothing of your context.

The Arrival of the “Week-Long” Agent

We are graduating from agents that run for minutes to those that operate for days or weeks. By the end of 2026, it will be normal to assign a research or legal task to an agent on Monday and receive the completed output on Friday. As these systems burn through millions of tokens recursively checking their work, humans will effectively become the bottleneck. Our role will shift from doing the work to defining the constraints and reviewing the output of these “agent colleagues.”

The Hard Split Between Personal and Work AI

The era of “bring your own AI” is ending. We will see a sharp divergence between personal AI, optimised for coziness and engagement, and professional AI, designed for compliance and rigour. Work environments will demand strict identity layers, audit trails, and data boundaries. You might chat freely with your personal assistant about your holiday, but the moment you enter the corporate environment, the system will become a regulated, logged, and secure entity. The firewall between these two worlds will become absolute.

Non-technical Work Adopts Engineering Disciplines

The line between “technical” and “non-technical” roles is dissolving. Marketing managers, HR directors, and operations leads will find their daily work resembling software engineering. They will need to write crisp requirements for agents, manage token throughput, and iterate on workflows. The ability to define a problem clearly enough for a machine to solve it will become the universal business skill.

The Power Law of Adoption

The gap between the AI-native and the AI-naive will become insurmountable. The top 5% of businesses are currently rebuilding their entire workflow around autonomous agents, preparing to move at speeds 10 to 100 times faster than their competitors. Companies that fail to adapt won’t just fall behind; they risk being ambushed by leaner, hyper-efficient startups that can ship products and react to market changes instantly.

From Reactive Tools to Proactive Partners

AI is shifting from a tool you pick up to a partner that taps you on the shoulder. We will see the rise of proactive assistants that notice when a project is stalling or when a human process is failing, and offer to intervene. This “proactivity” will become a key competitive battleground, with consumers potentially adjusting sliders to determine just how pushy they want their digital assistants to be.

The Great Retooling

The training requirements for 2026 will exceed the last twenty-five years combined. This is not just about learning new software; it is about learning a new way of working. Workers will need to master the art of leading hybrid teams of humans and agents, defining work for fleets of autonomous systems, and maintaining quality control in an automated environment.

The Engineering View: The Code Behind the Curtain

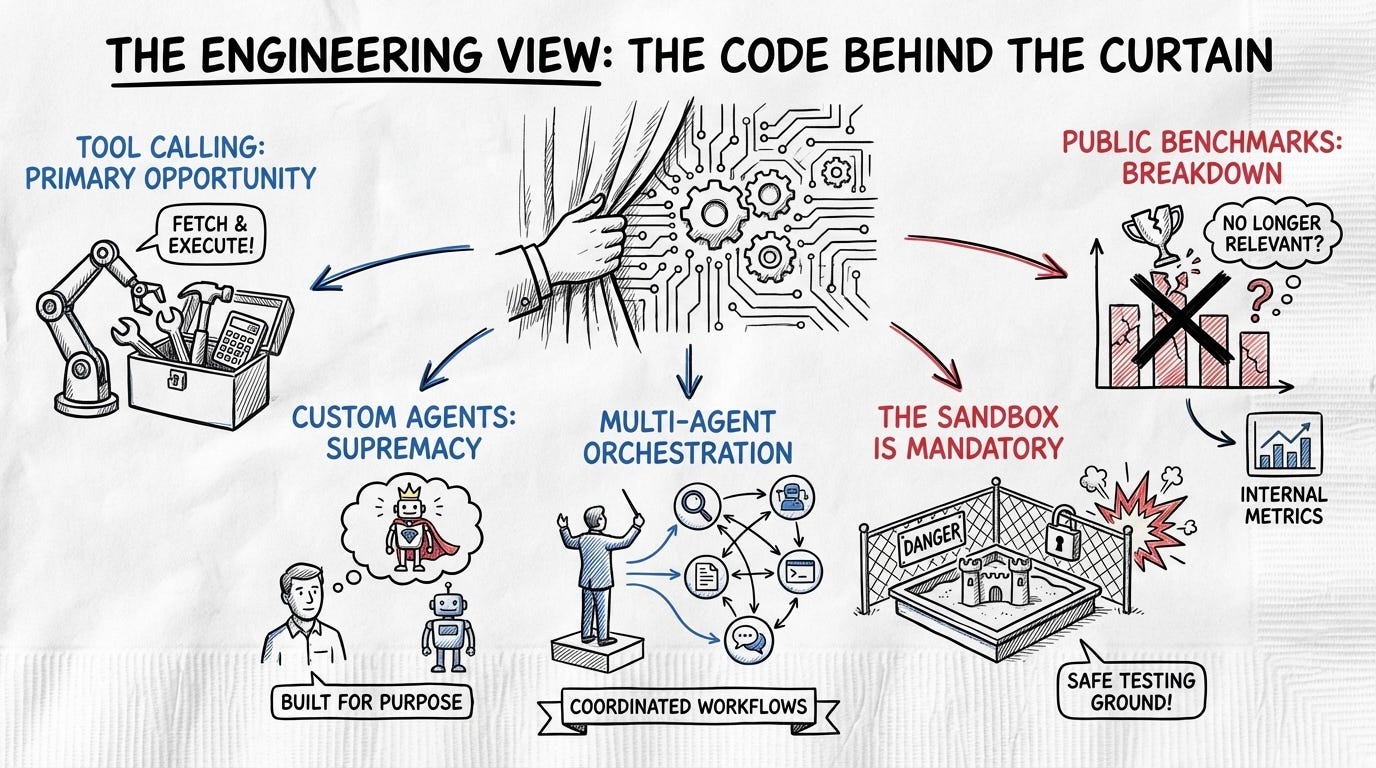

For the builders, 2026 represents a move away from generic “prompt engineering” toward rigorous system design. The focus shifts from the model itself to the orchestration around it.

Tool Calling as the Primary Opportunity

Currently, only about 15% of output tokens are “tool calls”—requests for the model to take an action like running a command or searching the web. This is the single biggest growth area. Tool calling is the bridge between a chatbot and a real-world agent. It turns the “big three” (context, model, prompt) into the “core four” by adding tools. Engineers who master this will be the ones building systems that actually do things, rather than just talking about them.

The Supremacy of Custom Agents

The top engineers are already moving away from generic, do-it-all tools. They are building small, custom agents designed to solve specific problems using bespoke SDKs. A custom agent, comprised of 50 lines of Python and a carefully crafted system prompt, can often outperform a massive, general-purpose application. These micro-agents are cheaper, faster, and easier to debug, making them the high-leverage investment of the year.

Multi-Agent Orchestration

We are moving beyond the single agent. The new frontier is orchestration, where an engineer might spin up ten agents to tackle a problem simultaneously. One agent plans, five execute, and four review the work. This “boardroom of bots” approach allows for cross-validation, where agents check each other’s homework, effectively hallucination-proofing the output and increasing reliability by orders of magnitude.

The Sandbox is Mandatory

To let agents run free, you need a safe cage. Top engineering teams will universally adopt agent sandboxes—isolated environments where code can be executed without risking the host machine. This allows for a “best of N” pattern, where you ask ten agents to solve a coding problem in their own private sandboxes, run the tests, and only present the user with the solution that actually works.

The Breakdown of Public Benchmarks

As every model starts hitting 90%+ on public benchmarks, those scores become meaningless noise. Smart engineering teams will stop looking at the leaderboard and start building their own private evaluation sets. The competitive advantage will come from knowing exactly how a model performs on your proprietary data and use cases, creating an information asymmetry that the public benchmarks can no longer provide.

The Road Ahead

If the last three years have taught us anything, it is that the pace of change is indifferent to our comfort levels. The transition to 2026 is a move from potential to kinetic energy. The models are smart enough, the agents are capable enough, and the economic incentives are strong enough. The question is no longer whether this technology will work, but who will have the courage to trust it with the keys to the business.

We are leaving the playground. It is time to get to work.